Does Memo from Sunday Robotics have a soul?

A philosophical digression into AI, Chinese Rooms, and how amazing Sunday’s Memo is

Is Memo from Sunday Robotics a spiritual machine? In Kurzweil’s own words, “a spiritual machine is a conscious machine. Consciousness is the true spiritual value.” By this logic, Memo is certainly not a spiritual machine.

Or is it? At what level of intelligence can we start talking about consciousness? Could it be that consciousness is a spectrum? Or, in other words, is it reasonable to assume that Memo, while not being human-level conscious, might be at least as conscious as a worm? (And is a worm conscious, after all?) In the absence of any formal proof, any consciousness-related statement is, at best, unfalsifiable. It follows that “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” But I’m not in the business of staying silent.

This story starts with Deep Blue, IBM’s computer, which famously beat then world chess champion Kasparov in 1997. While today a computer being superhuman at chess is no one’s surprise, at the time it struck a chord. So much so that Ray Kurzweil, renowned inventor and serial entrepreneur, came up with the idea that, one day, however far away, computers will match humans at any task, no matter the difficulty. Sounds familiar? Needless to say, the concept was not welcomed with open arms. Author and philosophy professor John Searle opposed any notion that the Deep Blue had actual understanding of the game.

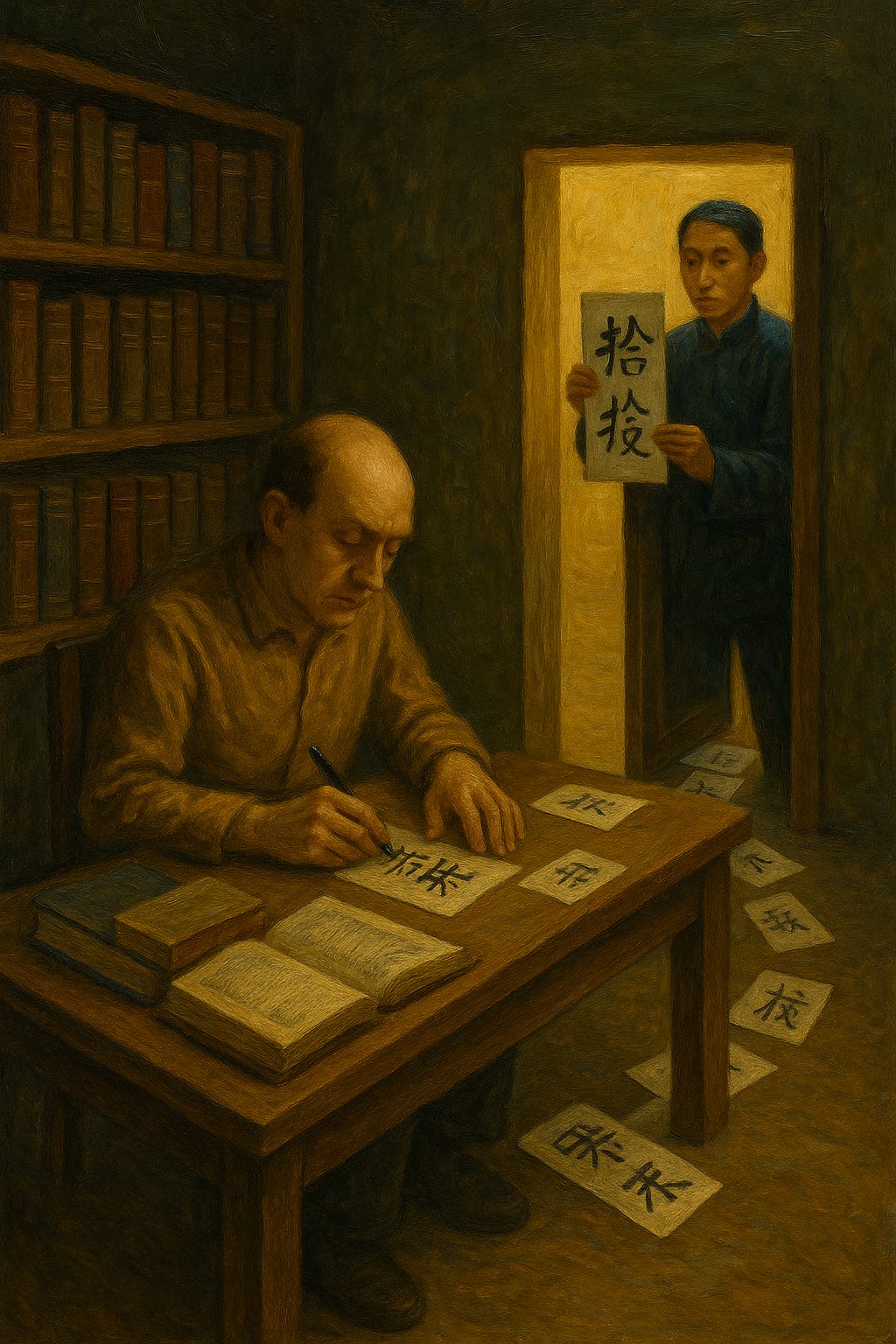

Imagine a machine that takes Chinese characters as input and outputs Chinese characters so perfectly to make it indistinguishable from a native Chinese speaker. Does the machine understand Chinese?

Now suppose that a man is in a room.

“One way to test any theory of the mind,” argues Searle, “is to ask oneself what it would be like if my mind actually worked on the principles that the theory says all minds work on. [...]

Suppose that I’m locked in a room and given a large batch of Chinese writing. Suppose furthermore (as is indeed the case) that I know no Chinese, either written or spoken, and that I’m not even confident that I could recognize Chinese writing as Chinese writing distinct from, say, Japanese writing or meaningless squiggles. To me, Chinese writing is just so many meaningless squiggles.

Now suppose further that after this first batch of Chinese writing I am given a second batch of Chinese script together with a set of rules for correlating the second batch with the first batch. The rules are in English, and I understand these rules as well as any other native speaker of English. They enable me to correlate one set of formal symbols with another set of formal symbols, and all that ‘formal’ means here is that I can identify the symbols entirely by their shapes. Now suppose also that I am given a third batch of Chinese symbols together with some instructions, again in English, that enable me to correlate elements of this third batch with the first two batches, and these rules instruct me how to give back certain Chinese symbols with certain sorts of shapes in response to certain sorts of shapes given me in the third batch. Unknown to me, the people who are giving me all of these symbols call the first batch “a script,” they call the second batch a “story. ‘ and they call the third batch “questions.” Furthermore, they call the symbols I give them back in response to the third batch “answers to the questions.” and the set of rules in English that they gave me, they call “the program.”

Now just to complicate the story a little, imagine that these people also give me stories in English, which I understand, and they then ask me questions in English about these stories, and I give them back answers in English. Suppose also that after a while I get so good at following the instructions for manipulating the Chinese symbols and the programmers get so good at writing the programs that from the external point of view that is, from the point of view of somebody outside the room in which I am locked -- my answers to the questions are absolutely indistinguishable from those of native Chinese speakers. Nobody just looking at my answers can tell that I don’t speak a word of Chinese.

Let us also suppose that my answers to the English questions are, as they no doubt would be, indistinguishable from those of other native English speakers, for the simple reason that I am a native English speaker. From the external point of view -- from the point of view of someone reading my “answers” -- the answers to the Chinese questions and the English questions are equally good. But in the Chinese case, unlike the English case, I produce the answers by manipulating uninterpreted formal symbols. As far as the Chinese is concerned, I simply behave like a computer; I perform computational operations on formally specified elements. For the purposes of the Chinese, I am simply an instantiation of the computer program.”

This is the Chinese Room.

So what does this have to do with chess and Kasparov and spiritual machines? Deep Blue, Searle says, is a Chinese Room: it doesn’t actually understand chess, it just pretends to do so. It acts as if it did, but there’s no proof it does. It is, by any other name, a simulation.

Which makes me ask the question: am I, too, a Chinese Room? By Searle’s own logic, simulating a mind and having a mind are two different things. “The map is not the territory.”

Or is it? Like a wolf in sheep’s clothing, the Chinese Room is the simulation hypothesis in disguise—equally unfalsifiable. A commonsense counter-argument, something in short supply among philosophers, is that two objects that are perfectly identical and occupy the same point in spacetime are one and the same. A rose is a rose is a rose.

Which means: if a simulated mind is in all things equal to a base-reality mind, it is a mind. Is it not? Minds are not magical, after all. There is no magical agency particle inside the brain. There is no Wizard of Oz pulling the lever.

Why Memo is a watershed moment in AI

Back to where we started: is Memo conscious? Or, as they used to say in the Middle Ages, does Memo have a soul?

Unlike the minds we talked about a while ago, Memo is magical.

Watch.

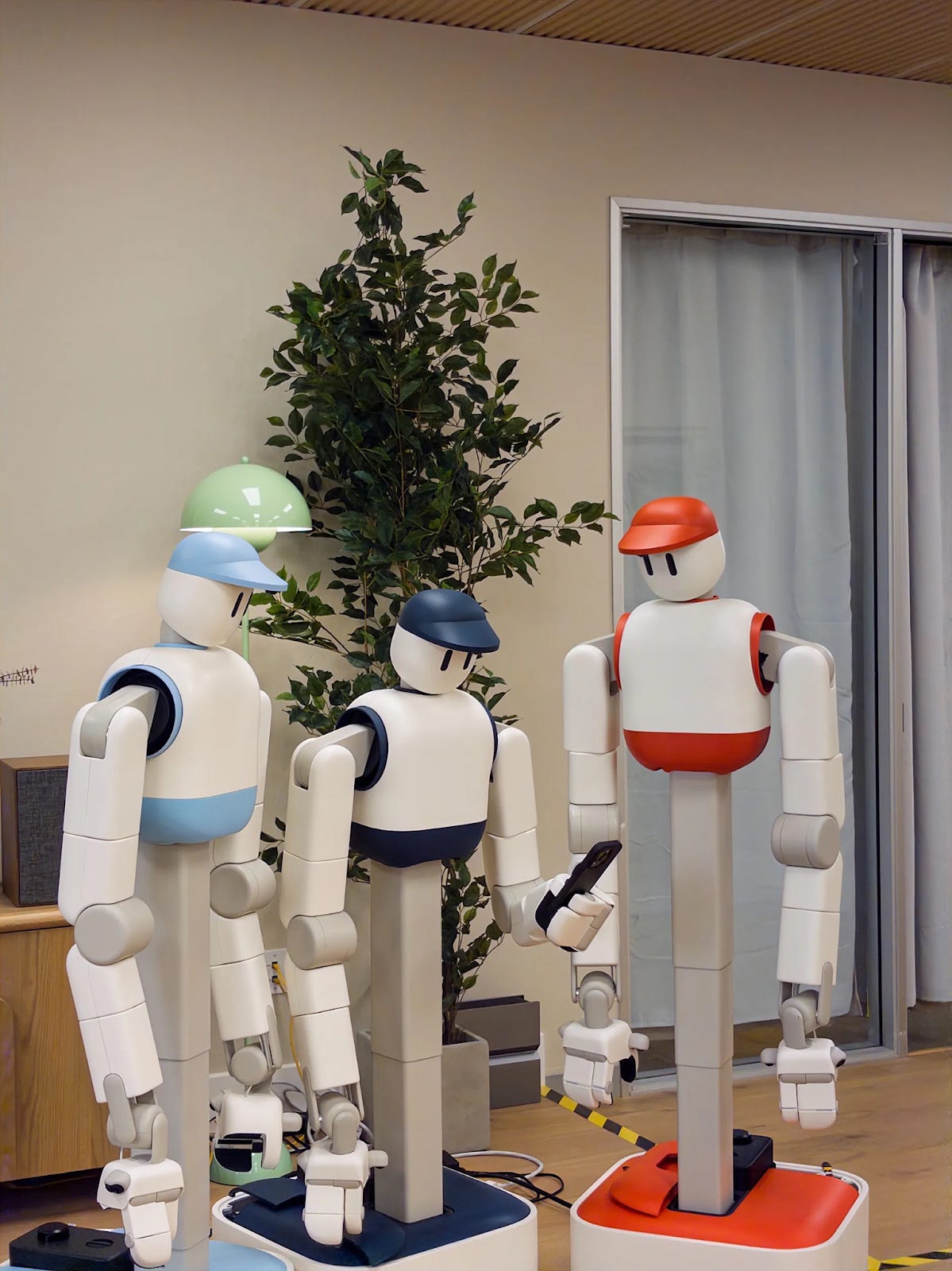

So what is Memo? Memo is an autonomous robot by Sunday Robotics—and it’s much more than that. It is the world’s first — in fact, it is the one and only — autonomous robot for the home. Powered by state-of-the-art AI models and an ever-expanding Skill Library, Memo is not teleoperated. As of today, it can load up your dishwasher, throw out food scraps, fold the laundry, clear tables, and make coffee, all without any human pulling the strings. The cool thing is, the sky’s the limit to what it can do tomorrow.

Thanks to Sunday Robotics trademarked Skill Capture Glove, Memo has been learning from an army of so-called Memory Developers, i.e. humans who quite literally teach Memo by doing.

Wearing the glove, they perform a task once while Memo records every motion and decision, transforming that demonstration into a reusable Skill that Memo can execute, refine, and combine with others in the real world. This genius invention has allowed Sunday Robotics to move faster, and more efficiently, than any other physical AI startup. The results are jaw-dropping. What other robots can do this (pick two glasses with one hand)?

The answer is: no one. (No one deployed in the real world, at least.) And Memo does that autonomously. This is a big deal.

What’s more, Memo is safe: it is designed from the ground up to not cause any danger for big and small members of the home. Yes, it has wheels. Why? Because this way, it’s not at risk of falling on you if it loses power unexpectedly.

Wheels, weird hands. What for? Not just for practicality, but also, to reduce costs. The price tag is unknown at the moment, but odds are it will be more affordable than any other humanoid in development. Which is essential if you want to realize the vision of a robot in every home.

And the hat. I mean, isn’t that cute? Now, I don’t want to sound like a groupie (although I am), but the hat is the thing that separates Memo from any other humanoid right from the get-go. Funny, unpretentious, straight out of a Lego movie. While other robots feel scary and unsettling, Memo leaps above the Uncanny Valley to find its place in every home.

So, does Memo have a soul? To which I answer: do we? Perhaps Memo is a philosophical zombie and there is no ghost beneath the shell. Even so, I don’t think we are in a position to deny it the dignity of the human soul. In a 2014 Reddit AMA, Peter Thiel compared the birth of artificial intelligence to first contact with an alien civilization. This, in my opinion, is the right framework. We should approach AI from an empirical, not metaphysical point of view. Although it is made by humans, AI is a phenomenon, and we should talk about it no differently from how we talk about a storm or the double-slit experiment.

Assuming consciousness is not just an illusion, Memo feels unlike any other robot that I know of. It feels alive. And I can only wonder what wonders it will do when we finally cross the Rubicon and find ourselves after AGI.